Semantic HTML and ARIA

Understand what native, semantic HTML is, how ARIA affects it, and when and how to use these technologies.

Overview

Semantic HTML provides meaning to the content of a web page. It involves using the correct HTML element for the job.

HTML has a concept known as "native semantics". This is metadata that is intrinsic to each HTML element.

Accessible Rich Internet Applications, commonly called ARIA is a way to augment or override this metadata in order to help assistive technology understand and take action on web content.

Why?

Many people and technologies benefit from properly-used semantic HTML.

Using the correct elements allows assistive technology to accurately convey the purpose and operation of content to the user. Without it, they will not be able to navigate and take action on web content.

Other benefits of using semantic HTML include, but are not limited to:

- Interoperability with different technologies (ex: pasting web content into Microsoft Word),

- Search Engine Optimization (SEO),

- Scraping and parsing for LLMs,

- Alternate modes of viewing content (ex: Reader Mode, Forced Colors Mode, etc.), and

- Code readability and intent.

Guidelines

For designers

In your designs, annotate what HTML elements should be used for various parts of the design, if appropriate.

Also reference other internal resources, such as office hours.

For engineers

Think about the content that will populate an element in order to determine what HTML element should be used.

Are you building a navigation? Use the nav element instead of nested div elements. You may need to add interactivity to more complex elements, such as dialog.

Some elements may require additional ARIA attributes to convey things such as state, but be careful to use these only when necessary.

Also reference other internal resources, such as office hours.

How to test for semantic HTML

HTML validators, automated tooling, unit tests, and linters are a few ways to test for proper HTML. Most automated tools can catch some incorrect usage of HTML elements. For example, if heading levels are out of order, it will be reported as a violation. Keep in mind that automated tools only catch around 20-25% of accessibility errors.

This is a subset of the tools available:

Validators

Automated tools

Linting

Common mistakes

Using improper elements to achieve the desired visual style

- Example: Using an

<h1>tag for a heading that should be an<h3>because the visual style of the<h1>is desired. - Solve: Use CSS for visual styling.

Using the title attribute

- Example: A

titleattribute placed on abuttonthat uses a string value of, "Create Issue, ⌘ ⏎". - Solve: It is inaccessible for many users, such as touch-only and keyboard-only users. Use other Primer patterns that accommodate this.

Using improper markup

- Example: Using a

divelement to trigger an action. - Solve: Using a

buttonelement instead.

Using incorrect ARIA

- Example: Using an

aria-labelon a non-interactive element such as a<div>. - Solve: Only use ARIA when necessary, and if you can use a native HTML element, you should. More information on this guidance.

Duplicate IDs

- Example: Two elements on the page with

id="anchor". - Solve: Use unique IDs for every element on the page.

Decorative elements not marked as decorative

- Example: An avatar for a user listed immediately before their user name.

- Solve: Add

role="presentation"oraria-hidden="true"to elements that are for decorative purposes only.

Deep dive

Following is more information and context about semantic HTML and ARIA.

Native semantics

Each HTML element in the specification has what is known as “native semantics.” These native semantics are part of element’s intrinsic metadata.

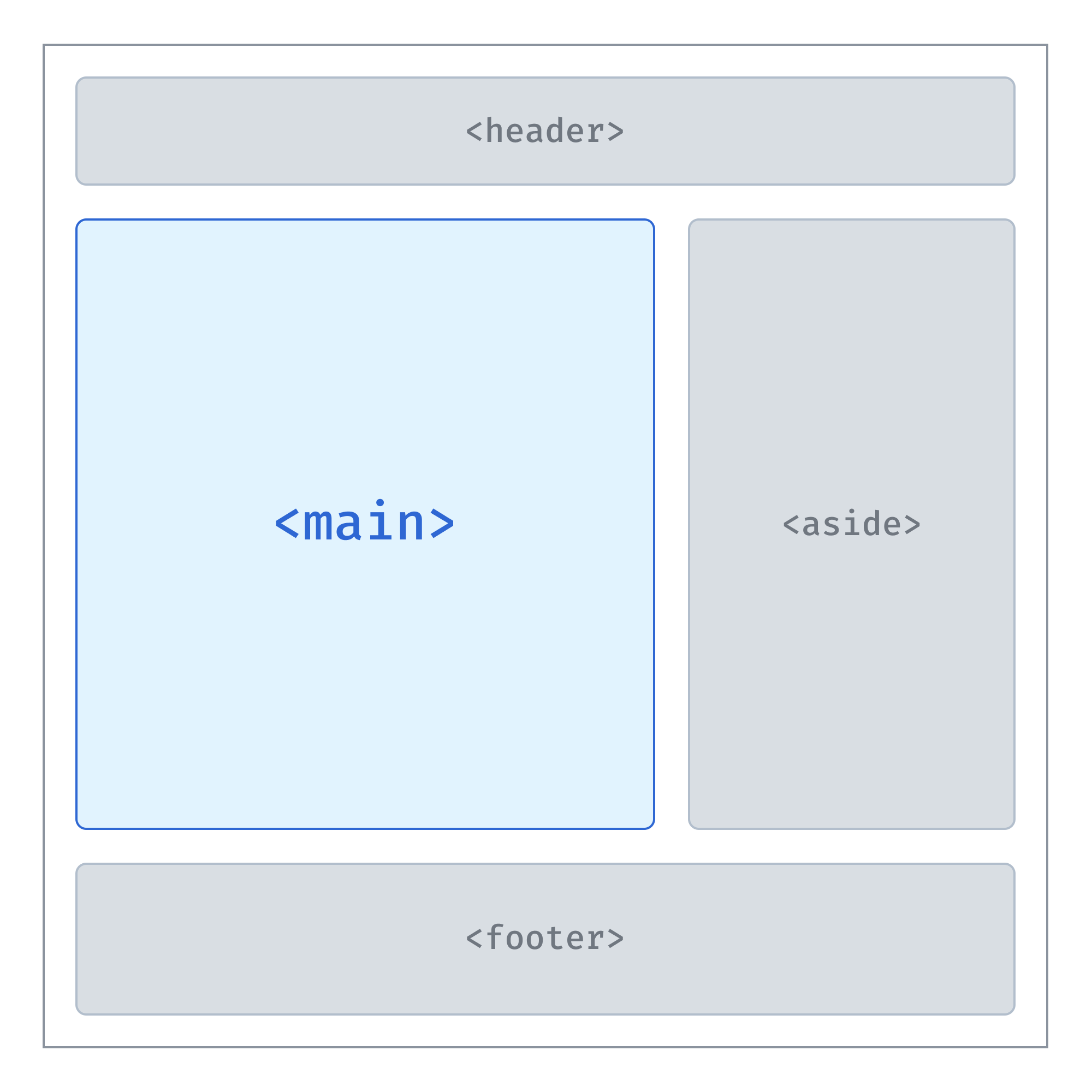

For example, when you use the main element, you as a human understand that you’re demarcating an area and assigning it a very specific meaning: The main content area in a design.

Using the main element also programmatically communicates to browsers and assistive technology that this is a main content area.

This programmatic communication allows software such as screen readers to be able to scan the code making up a page or view, and generate announcements that allow its user to understand:

- Where they are,

- Where they can navigate to, and

- What actions they can undertake.

Another example would be an ordered list. The implicit role of a ol element communicates:

- There is a list, and

- Its order is significant.

Using a li element within the list communicates that it is one in a series of list items. This allows assistive technology to announce:

- The presence of a list,

- How many list items are present, as well as

- Other pertinent information.

Both of these examples are important because if you cannot see the design of the page, you need a mechanism to communicate the same quality of experience as someone who can see the screen. Many screen readers also provide the ability to navigate by element, for example jumping from heading to heading to understand the overall content present.

Semantic metadata

In accessibility, native semantics map to three important pieces of metadata:

- Name: How a control is announced (ex: “Phone number”).

- Role: What a control is (ex: “Input”).

- Value: Optional user-supplied information for the control (ex: 1-900-MIX-A-LOT).

These metadata attributes are important enough that they have their own Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) success criterion (SC). SC 4.1.2: Name, Role, Value is level A, meaning it applies to all websites and web apps evaluated for accessibility.

The origin of native semantics

Assistive technology predates the internet. The way software such as a screen reader can understand and take action on a computer’s operating system and installed applications is via parsing the metadata associated with the building blocks used to construct UI.

The way to recreate this process on the web is via HTML.

As a technology, HTML is designed to assign meaning to content, with that meaning being both:

- Human-facing and

- Machine-facing.

Human-facing meaning is the single word names used for HTML elements. Machine-facing meaning is the metadata associated with each HTML element.

By this mechanism:

- Developers understand intent by reviewing the elements used to build the DOM, and

- Assistive technology understands what format the content is presented in, as well as how you can interact with it.

This translation of human-facing meaning to machine happens with a device’s accessibility tree.

Implicit roles

Part of each element’s native semantics is its role. A role is the mechanism that communicates what the element is supposed to represent or do.

The roles included with every HTML element are considered implicit, in that they are applied by virtue of just using the HTML element—this is what makes assistive technology announce the presence of an ordered list when you use the ol element.

The list of all current HTML elements, as well as their implicit roles can be found in table, Rules of ARIA attribute usage by HTML element, published in the ARIA in HTML specification.

HTML is accessible by default

This phrase is a bit of a misleading statement.

As the previous section alludes to, HTML is a method for describing content in a way that it can be parsed by assistive technology.

Why isn't my HTML accessible?

There are two factors to consider:

- It relies on the HTML elements and attributes you use having good support with assistive technology.

- Wrapping content in a description is a human act, and it requires the element being used to be both relevant and accurate.

1. Good support with assistive technology

Certain elements and attributes do not interface well with assistive technology, and are consequently not reported accurately to the user, or reported at all.

For example, the title attribute has poor support with assistive technology. It is not fully keyboard accessible, and can also easily and unintentionally can override the intended accessible name of the element it is applied to.

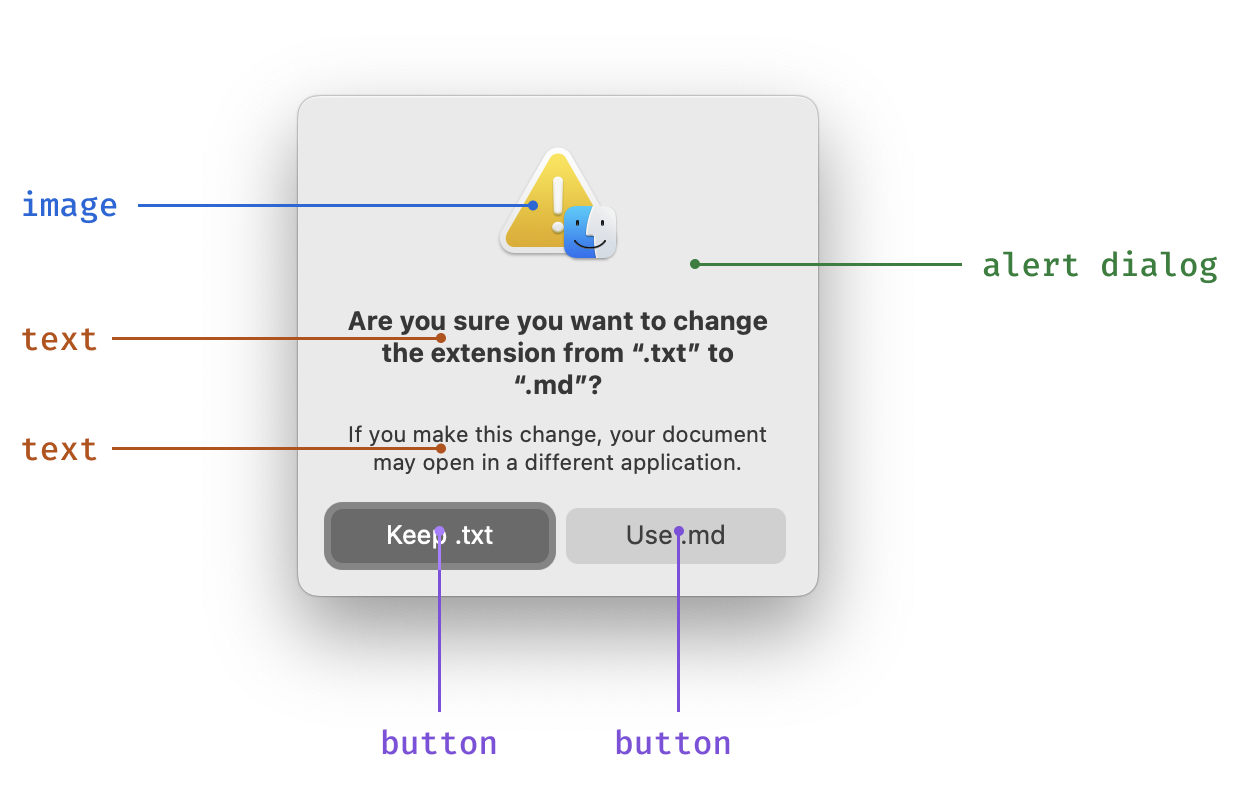

Up until very recently, the dialog element was also not supported by most major forms of assistive technology. Fortunately, its support has increased, but the slower, risk-avoidant upgrade curve of assistive technology users should still be considered.

2. A relevant and accurate description

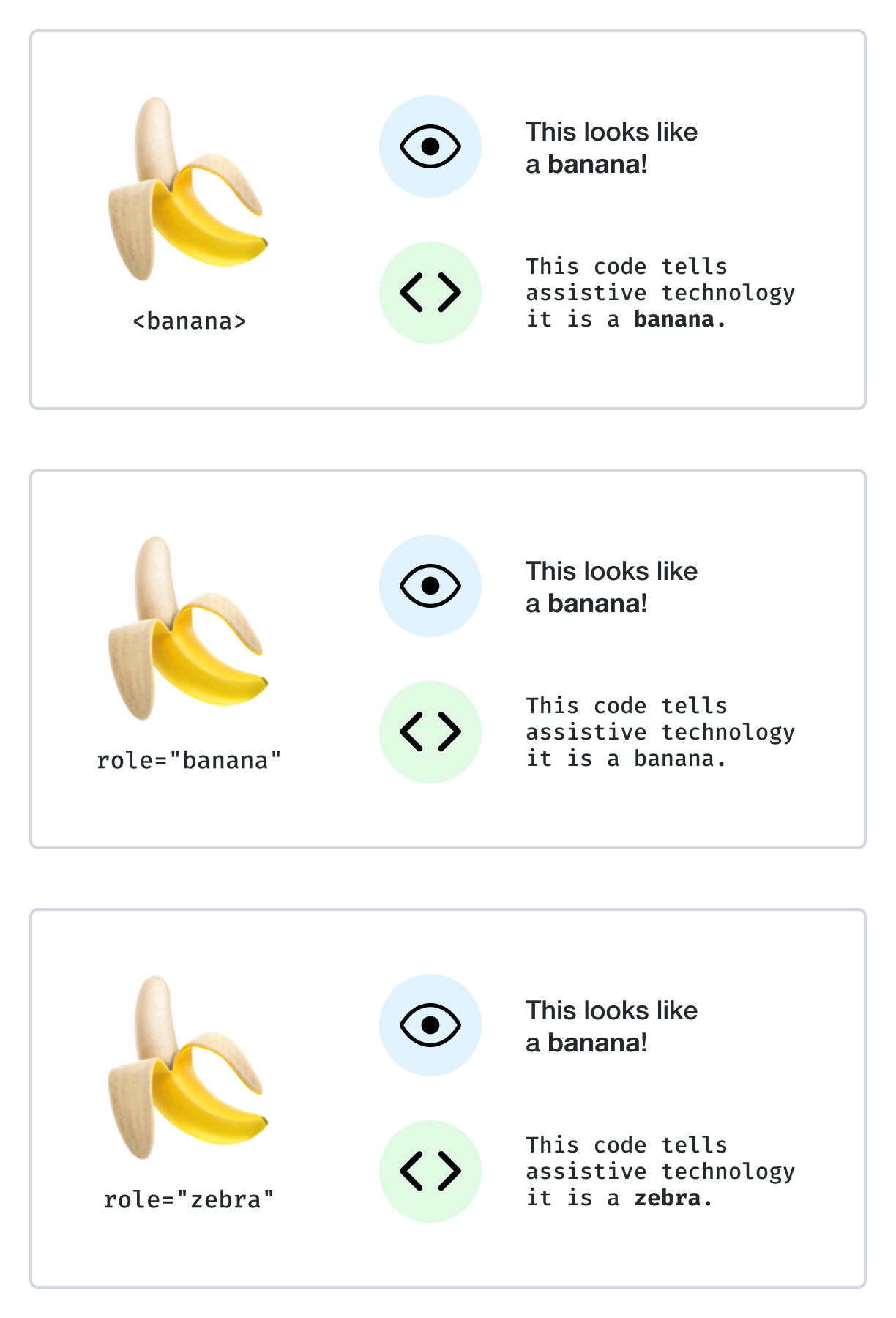

A good way to think about this is describing a banana as a zebra.

You have technically assigned the fruit a description for others to understand, it’s just that the description is inaccurate. You can tell someone it is a zebra, but they'll still visually see the banana. Because of this, misinterpretation and misunderstandings will occur.

Relevant and accurate descriptions can be provided in two ways:

- Using the most applicable HTML element, or

- Overriding an HTML element's implicit role with an explicit ARIA role declaration.

Reading order

Screen readers and other assistive technologies convey the information to the user in the order that it is marked up in the code, not necessarily how it looks on the page.

Ensure the order matches a logical order of information presented. One way to verify this is to view the page without styles and see if the order of content is logical.

ARIA

ARIA is an extension of HTML. ARIA was designed as a way of extending HTML’s functionality for situations where base HTML’s semantics could not be used to accurately describe interactive behavior.

ARIA allows you to supplement or override HTML’s default behavior. It does this by providing a suite of predefined attributes that you can declare on HTML and then modifying via JavaScript.

For example, the aria-expanded attribute allows you to programmatically communicate if something is in an expanded state (aria-expanded="true"), or collapsed state (aria-expanded="false"). When applied to a button element, it extends the element’s native semantics to communicate:

- This is a button, activating it will perform an action, and

- The UI the button affects is currently in a non-expanded state.

The text string used for the button is the final piece of the puzzle. It describes what content will be expanded when activated, and then collapsed when activated again.

Here is a sample screen reader announcement, showing how this information is used to create meaning:

Button, expanded. Personal information.This announcement tells us:

- There is a button,

- Activating the button toggles content,

- The content it controls is currently toggled into an expanded state, and

- The content toggled into an expanded state by the button deals with personal information.

This announcement reflects what a user who can see the screen will know when looking at the visual UI of the page, creating an equivalency of experience between the two modes of operation.

Note that the hiding of the content in the widget in a collapsed state needs to be done via other HTML or ARIA declarations, JavaScript logic, and CSS styling.

The first rule of ARIA

In addition to its grammar and syntax, ARIA has explicit rules that govern its usage. The first rule of ARIA states:

If you can use a native HTML element or attribute with the semantics and behavior you require already built in, instead of re-purposing an element and adding an ARIA role, state or property to make it accessible, then do so.

The reason this rule exists is that HTML has a far wider range of support across different operating systems, browsers, and assistive technologies—all which have to work together to function.

A good way to think about this is trying to use newer syntax on a version of a programming language released before the new syntax was introduced. Your code will not work, as the language does not understand the syntax you are supplying it.

The different categories of ARIA roles

There is an underlying hierarchy and structure to ARIA. The categories are:

- Abstract roles. Not for use in code. These roles are used to define overall language taxonomy

- Widget roles. These roles are used to define atomic, standalone UI such as individual radio buttons, tabs, menu items, etc.

- Document structure. These roles are used to define largely non-interactive content that organizes content on a page. This includes content like headings, images, table cells, etc.

- Landmark roles. These roles are used to define overall areas of the page such as the main content, the header and footer, sidebar, etc.

- Live Region Roles. These roles are for making announcements to assistive technologies.

- Window roles. These roles are used for browser-level UI chrome such as alerts.

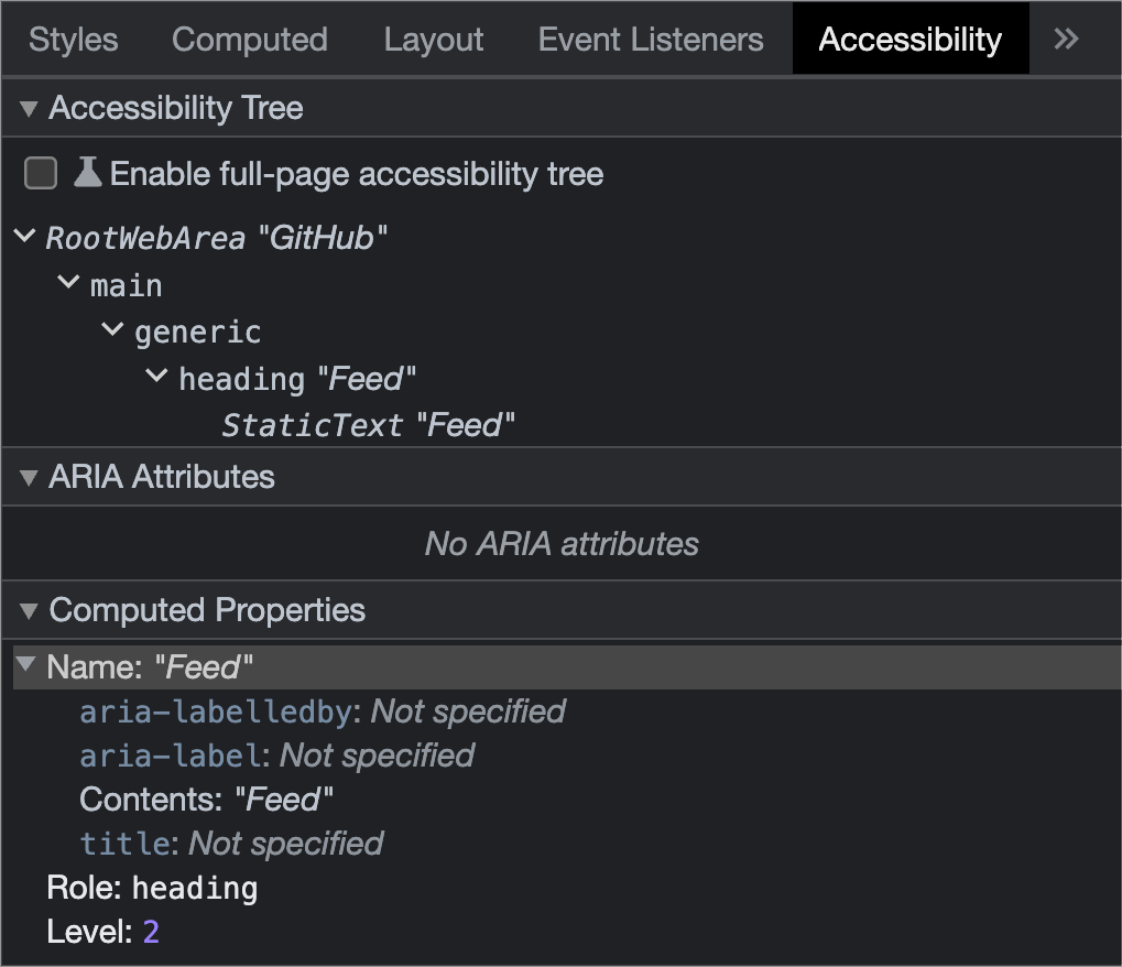

How do I determine an HTML element’s role?

The most effective way to determine an HTML element’s role is to use the browser’s inspector tools.

In Chromium browsers, the secondary panel (used for listing styles, computed information, event listeners, etc.) has an overflow option for Accessibility. Highlighting an HTML element in the DOM will display its role.

For example, the “Feed” heading on the logged-in GitHub homepage uses a h2 element. Inspecting it will reveal a role of heading in the Accessibility inspector panel.

The Accessibility panel functions a lot like the Computed panel. What is reported there is what the browser calculates after all content and logic is parsed, which is what assistive technologies ultimately use to communicate with their user.

Do I need to declare a role on an HTML element?

Most of the time you should rely on an HTML element’s implicit role, and not manually declare a role. This is why picking the most appropriate and descriptive HTML element is so important.

Why can’t I use spans and divs for everything?

As mentioned earlier, HTML elements have a far wider and deeper range of support across multiple operating systems, browsers, and assistive technologies, and versions of each.

Furthermore, declaring ARIA does not automatically add functionality. For example, declaring role="button" on a div element does not confer any of the behavior a button element possesses—such as being able to be used by keyboards. In this example, this means assistive technology will report the presence of a button, but the construct will not allow a user to take action on it.

In some cases HTML elements also contain behaviors that cannot be replicated or polyfilled by JavaScript. Examples of this are keydown exploration with buttons, Reader Mode parsing, etc.

Unknown contexts and specialized modes

There are many ways a user can modify their browsing experience without expressing a programmatically detectable flag. In addition, web content is often consumed in experiences other than browsers.

HTML element metadata—and not ARIA declarations—will hold up far better when consumed in non-standard contexts. Examples of this are user-facing scripting, pasting into supporting applications, and third party browser modifications like extensions.

Additionally, specialized modes such as Reader mode and Forced Color mode rely on HTML as a way to function.

Performance

Another consideration is that implicit roles are far less computationally intensive than ARIA declarations. This is due to how assistive technology scans, interprets, and calculates digital content.

In extreme cases, too much ARIA can actually overwhelm and crash assistive technology. In less extreme cases, it can cause delays between user action and announcements. The range of these delays can be annoying to unusable.

Progressive enhancement

Most ARIA is also intended to be applied and modified via JavaScript. If you are building with a progressive enhancement approach, using relevant HTML elements helps to ensure a usable baseline experience even in less than ideal situations.

Style normalization

In addition, Primer provides styling resets to normalize default HTML element appearance and behavior across different web browsers.

This normalization means less-to-no friction for ensuring the HTML elements you use appear and behave consistently across different browsers.

What happens when I try to make a non-interactive element interactive?

You can technically apply an interactive role such as button to a div element.

While this will cause the div to be announced as a button by assistive technology, its declaration does not confer any of the qualities the button element does. Some, but not all of these qualities can be recreated by JavaScript.

Because of this, prefer using native interactive elements rather than declaring interactive roles on non-interactive elements.

What happens when I try to make an interactive element non-interactive?

Suppressing an element’s native interactive behavior is discouraged. It may lead to broken or confusing behaviors.

ARIA and explicit role assignment

There are scenarios where a HTML element’s role should be explicitly assigned. The situations where you would want to intentionally modify an element’s role are when you:

- Are using a “newer” HTML element that has less browser support (not applicable with evergreen browsers/GitHub’s support matrix).

- Cannot control what HTML elements are being used (third party widgets, etc.).

- Are using

divorspanelements, which have an implicit role ofgeneric. - Use JavaScript logic for interactive behavior that necessitates a role modification in response to user or application manipulation.

- Creating complicated interactive widgets that have no native HTML equivalents (tabs, grids, menus, etc.).

Of the situations outlined, manipulation of roles with JavaScript logic is the most desirable. The previous situations are usually indicative of situations where larger concerns are present.

An example of this is Primer’s deprecated CSS tooltip. The construct used aria-label declared on a div element to create a tooltip effect that was visible to mouse and trackpad users. However, this construct was not accessible for keyboard and screen reader users.

Attempting to fix the immediate automated accessibility error ignored the larger problem that an interactive button element should have been utilized in place of the div.

What happens when I explicitly declare a role on a HTML element that matches its implicit role?

You may come across declarations from time to time where the explicitly declared role matches the element’s implicit role.

For example:

<footer role="contentinfo">In this code example, footer has an implicit role of contentinfo, but also has an explicit declaration of role="contentinfo".

role="contentinfo" predates the creation of the footer element. When footer was introduced in HTML5, the declaration of <footer role="contentinfo"> was used as a bridge until assistive technologies could be updated to support this new element.

Functionally, the explicit role declaration overrides the implicit role, but because the explicit and implicit roles match there is no difference for the assistive technology user.

These types of declarations are not advised and do largely not need to be made anymore, as nearly all assistive technology now supports HTML5. This includes all technology in GitHub’s assistive technology support list (staff link).

If you want to update these kinds of declarations, there are two factors to consider:

- Does the element output the intended role in the Accessibility inspector?

- Does your browser and assistive technology support criteria support this declaration?

What happens when I declare a role on an HTML element that isn’t allowed?

HTML is extremely fault tolerant.

One of the ways this manifests is that the browser will attempt to parse and render illegal or malformed declarations. This is done by heuristics that try to automatically detect and repair commonly misdeclared declarations.

The way this manifests is content that visually renders as intended, but will not be properly parsed by assistive technology. This is different from JavaScript and other programming languages where an error shows up in the console.

An example of this could be trying to make an image element into a heading:

<!-- ❌ Example only, don't do this -->

<img

alt="Our services"

role="heading" />Each element has a list of ARIA roles that are allowed. For our example, an img element with a non-null alt attribute only allows:

button,checkbox,link,menuitem,menuitemcheckbox,menuitemradio,option,progressbar,radio,scrollbar,separator,slider,switch,tab, ortreeitem.

Allowed roles are listed in the “ARIA roles, states and properties which MAY be used” column in the “Rules of ARIA attribute usage by HTML element” table located in the Document conformance requirements for use of ARIA attributes in HTML section of the ARIA in HTML specification.

How do I fix axe violations for aria-required-children and other similar error messages?

Certain HTML elements have parent/child relationships. For example, the li element needs an ol or ul element as its parent to communicate what kind of list item it is (ordered or unordered).

As ARIA roles provide a way to recreate implicit roles explicitly, its structure mirrors HTML. This means that certain ARIA roles expect certain HTML elements or ARIA declarations to be present as child elements in the DOM.

As mentioned earlier, constructs that use illegal or incomplete declarations will still render visually due to the fault-tolerant nature of the browser. There is no error that is thrown in the console, or alert dialog that will be displayed on DOM render.

The list of ARIA attributes that require specific child elements are:

aria-activedescendant,aria-controls,aria-flowto,aria-owns,aria-posinset,aria-setsize, androle="combobox".

The complete list of what HTML elements and ARIA attributes are supported as child declarations is too expansive to list, due to possible potential configurations. Because of this, it is encouraged to reference the documentation for each attribute to determine its child element or role criteria.